Not from My Garden: O’Keeffe’s Flower Paintings

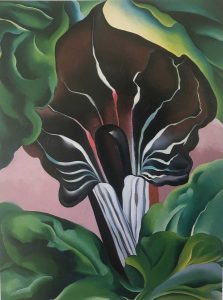

By Eugenia ParryIn 1940 Georgia O’Keeffe, then 52, wondered whether she was so attached to her own world that she couldn’t see anything else.[1] It was the confession of a visionary. Seeing wasn’t recording. She was referring to an inner vision, permanent and sublime, altering all rational intentions. It had taken her years to recognize that her strength as an artist lay in this ability to see from within. Stieglitz didn’t get it. He told her she was a modernist, an abstractionist. For a long time she believed him. “It was his game,” she remembered, “and we all played along or left the game.”[2]During the 1920s, when she had to produce an artist’s statement about her flower paintings, she hid behind a battle with the New York public: she claimed people were too busy and had no time to stop and look at anything as lowly and simple as a flower, so she had decided to “surprise” Gotham by making her flowers “big.” Again she sold herself short. Flowers were thresholds of her deepest intimacy with the universe, but she wouldn’t admit it. Her feckless words explained nothing. We’re used to seeing O’Keeffe’s flower paintings as decorative motifs on posters promoting cultural events, which has dulled the works’ original power. These works are not depictions of plants. The most memorable of them, from the 1920s, are fierce forays into the unconscious. Feeling her way into a flower was an adventure for O’Keeffe. Staring into an anemone or a black iris, she was a wide-eyed child slowly entering a dark wood. Close-up, flowers ceased to be the stuff of nosegays or gardens. They almost ceased to be things and became events. Exploding their frames, they are force fields enacting sublime dramas of the soul. No one had addressed flowers this way. Describing her flower passion in 1926, she trembled: “You put out your hands to touch it, or lean forward to smell it, or maybe touch it with your lips almost without thinking….” [3] Red cannas, devouring flames of desire, rage and crackle like wildfire. Yellow sweet peas, joined to yellow cactus flowers, twist and grimace. Black pansy vies with pale blue forget-me-not. Black hollyhock spars with larkspur. A white rose encircled by uncanny light is Venus, Georgia’s evening star. White iris sticks out its tongue. A collapsing petunia becomes a pile of purple velvet whose folds start to resemble a canyon. Or chambers of the heart. Poisonous jimson weed is a gyrating dancer. The inner sancta of oriental poppies contain black tarantula faces that seek our attention and want to converse. Jack-in-the-pulpit is a sexual predator. Black Iris VIis a gaping death’s head.Not all of O’Keeffe’s flower paintings behave this way. The definitive illustrated catalog of her work includes plenty of simple, descriptive flower studies, many inert and rather dull, like works dutifully executed in a still-life class. They don’t betray how flowers made her feel, the trouble she took to get to know them, or how their dramas lead us into states of mind. In the best paintings, flowers interconnect with everything else: the seasons, the motions of heaven and earth, the music of the spheres. It’s not surprising that she would float a gigantic flower over an arid mountain landscape, stressing the equation of opposites, how each needed the other.O’Keeffe made the mistake of thinking that if she made her flowers large enough the public would see what she saw. She never developed this idea in writing. The paintings say it all. With her nose buried in pollen, she got too close. The forms of her flowers were not only floral; they began to resemble everything in nature that lived and moved. Her patrons couldn’t see beyond their own sexual associations—to them, the flowers resembled female genitalia. The idea horrified her, though she was no prude. What she abhorred were simplistic, Freudian accusations. She fumed: they “hang all [their] associations with flowers on my flower[emphasis added] and claim that I feel what I don’t.”[4]All this plants the idea that O’Keefe’s “big” flowers are dramatic theaters, mirroring the way we breathe, dance, stare, cower, and weep. They are gorgeous incursions into the secret recesses of many species in the universe they share. She titled a bird-of-paradise painting Not from My Garden[5], meaning, I presume, that she hadn’t grown it. Her most potent flower pieces aren’t drawn from anyone’s garden. They’re from inside her head. By the 1940s, she described herself as having in her world “more sky than earth.”[6] This recognition explains the majesty of her imagination, for at her best, she was less a painter than a magical image maker. She elevated flowers into oracles. Peering into them, we get a shower of pollen and receive answers to our most heartfelt questions.Notes:

We’re used to seeing O’Keeffe’s flower paintings as decorative motifs on posters promoting cultural events, which has dulled the works’ original power. These works are not depictions of plants. The most memorable of them, from the 1920s, are fierce forays into the unconscious. Feeling her way into a flower was an adventure for O’Keeffe. Staring into an anemone or a black iris, she was a wide-eyed child slowly entering a dark wood. Close-up, flowers ceased to be the stuff of nosegays or gardens. They almost ceased to be things and became events. Exploding their frames, they are force fields enacting sublime dramas of the soul. No one had addressed flowers this way. Describing her flower passion in 1926, she trembled: “You put out your hands to touch it, or lean forward to smell it, or maybe touch it with your lips almost without thinking….” [3] Red cannas, devouring flames of desire, rage and crackle like wildfire. Yellow sweet peas, joined to yellow cactus flowers, twist and grimace. Black pansy vies with pale blue forget-me-not. Black hollyhock spars with larkspur. A white rose encircled by uncanny light is Venus, Georgia’s evening star. White iris sticks out its tongue. A collapsing petunia becomes a pile of purple velvet whose folds start to resemble a canyon. Or chambers of the heart. Poisonous jimson weed is a gyrating dancer. The inner sancta of oriental poppies contain black tarantula faces that seek our attention and want to converse. Jack-in-the-pulpit is a sexual predator. Black Iris VIis a gaping death’s head.Not all of O’Keeffe’s flower paintings behave this way. The definitive illustrated catalog of her work includes plenty of simple, descriptive flower studies, many inert and rather dull, like works dutifully executed in a still-life class. They don’t betray how flowers made her feel, the trouble she took to get to know them, or how their dramas lead us into states of mind. In the best paintings, flowers interconnect with everything else: the seasons, the motions of heaven and earth, the music of the spheres. It’s not surprising that she would float a gigantic flower over an arid mountain landscape, stressing the equation of opposites, how each needed the other.O’Keeffe made the mistake of thinking that if she made her flowers large enough the public would see what she saw. She never developed this idea in writing. The paintings say it all. With her nose buried in pollen, she got too close. The forms of her flowers were not only floral; they began to resemble everything in nature that lived and moved. Her patrons couldn’t see beyond their own sexual associations—to them, the flowers resembled female genitalia. The idea horrified her, though she was no prude. What she abhorred were simplistic, Freudian accusations. She fumed: they “hang all [their] associations with flowers on my flower[emphasis added] and claim that I feel what I don’t.”[4]All this plants the idea that O’Keefe’s “big” flowers are dramatic theaters, mirroring the way we breathe, dance, stare, cower, and weep. They are gorgeous incursions into the secret recesses of many species in the universe they share. She titled a bird-of-paradise painting Not from My Garden[5], meaning, I presume, that she hadn’t grown it. Her most potent flower pieces aren’t drawn from anyone’s garden. They’re from inside her head. By the 1940s, she described herself as having in her world “more sky than earth.”[6] This recognition explains the majesty of her imagination, for at her best, she was less a painter than a magical image maker. She elevated flowers into oracles. Peering into them, we get a shower of pollen and receive answers to our most heartfelt questions.Notes:

- Extracted from the artist’s statement in a 1940 exhibition brochure; cited in Barbara Buhler Lynes, Georgia O’Keeffe(Yale, 1999), vol. II, appendix I, p. 1099.

- Cited in “That Memory or Dream Thing I Do,” by Eugenia Parry, in Georgia O’Keeffe: Visions of the Sublime (Torch Press/International Arts, 2004), p. 8, note 74.

- Statement from a 1926 exhibition catalog, as reprinted in Anita Pollitzer, A Woman on Paper: Georgia OKeeffe(Simon & Schuster, 1988), p. 189.

- Statement from a 1939 exhibition brochure; cited in Lynes, vol. II, appendix I, p. 1099.

- Lynes, vol. II, cat. no. 1506.

- Statement from a 1944 exhibition brochure; cited in Lynes, vol. II, appendix I, p. 1099.