The First Thanksgiving

By: Peggy RudbergTurkey is the centerpiece of modern Thanksgiving, America’s second favorite holiday after Christmas. But the menu of the original gathering was much simpler than our current feasts tend to be. And, as we now know, the relationship between the colonists and the Indians who shared in that first harvest meal was more complex than has often been portrayed.When the Mayflowerreached America in December of 1620, it was months behind schedule. The ship was carrying English Puritan separatists, who had been living in the Netherlands, where they enjoyed freedom of religion but had not met with financial success, as well as other colonists, indentured servants, and a crew of around thirty. Rough seas had forced them north of their destination, today’s New York City, where they had hoped to establish a trading post.Landing in Cape Cod Bay, they sought refuge in an abandoned Wampanoag village, which they named New Plymouth. Native people had lived in the area for more than 10,000 years but had been decimated by an epidemic brought by European traders beginning in 1616. During the freezing winter weather, the colonists lived onboard, where their stores of grain, dried meat, cheese, and biscuits were depleted; contagious diseases in crowded quarters reduced their number from more than a hundred to half that. Only four adult women remained alive by the time they disembarked, in March of 1621.A Wampanoag Indian named Tisquantum, who had learned English after being abducted by an English explorer, befriended the colonists. He facilitated an agreement of cooperation and military alliance between the colonists and the Wampanoag, whose diminished population had made them vulnerable to rival tribes. More importantly Tisquantum ensured the colonists survival by sharing knowledge of edible indigenous plants, how to catch fish and gather shellfish, and how to sow, fertilize, and harvest corn and other vegetables. Although many colonists came from agricultural backgrounds, they were ill-prepared to clear and farm the wilderness.The following fall the settlers had a successful harvest of corn and were preparing a traditional fall feast. Their gunfire, both from hunting fowl and from celebrating, drew the Wampanoag chief, along with 90 warriors, who believed the colonists were being attacked. The warriors were then invited to join in the meal; they augmented the offerings with five deer.Was turkey the centerpiece of the 1621 harvest meal that came to be known as Thanksgiving? Wild turkey was said to have been “in great store” that fall, but the only written description of the feast lists waterfowl, probably goose or duck, and venison provided by the Wampanoag. The colonists brought no large animals from England; only two dogs are recorded.The other food mentioned was maize, or corn, which along with beans had worked their way north over trade routes from Mexico 1,000 years earlier. New England Indians had shortened the growing season of corn by planting kernels from the earlier developing lower joints of the corn stalk. Controlled burning was used to clear their fields and corn and beans were planted with wooden tools, primarily by women, in rows of mounds with squash in the furrows. The natives cooked corn and beans together in a succotash and made unleavened bread with corn flour.Indigenous squash and melon was probably served, but there was no pumpkin pie. The settlers had not been able to grow wheat for flour and lacked shortening for a crust. Plus they had not yet built baking ovens. And while berries, fruits, nuts, and roots were plentiful for gathering, there was no cranberry sauce either. The Indians used cranberries medicinally, but this was 50 years before the sugar necessary to make them palatable would be plentiful.Potatoes, native to South America, had been brought to Europe by the Spanish but had not yet traveled to North America. Other root vegetables, such as turnips, carrots, and Indian cucumbers, had been introduced to the colonists and may have been included.The feast continued for three days. Unfortunately this goodwill and cooperation between Plymouth and the Indians did not last. As hundreds of new settlers arrived, land disputes arose, leading to broken treaties, bloodshed, and the displacement of native populations. So this Thanksgiving, remember America’s original inhabitants, and give thanks for your good fortune. How Turkey Got Its NameTheories of how Meleagris gallopavo, a bird native to the Americas, got its English name of “wild turkey” stem from convoluted colonial trade routes. Fifteenth-century Turkish merchants imported a type of fowl from Africa to Europe, where it was called “turkey cock.” When Spanish conquistadors imported domesticated M. gallopavo, bred from wild birds by indigenous Mesoamericans centuries before European exploration, confusion between the African fowl and the Spanish avian import led to calling them both turkeys. When English colonists reached America they were astonished to find a wild version of the familiar M. gallopavo.References:Gambino, Megan. What Was on the Menu at the First Thanksgiving?, Smithsonian.comGrace, Catherine O'Neill. 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving(National Geographic Society, 2001)Native Tech, Native American History of Corn

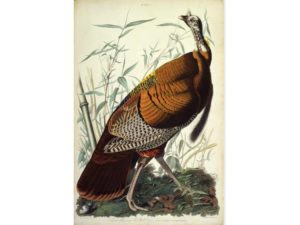

How Turkey Got Its NameTheories of how Meleagris gallopavo, a bird native to the Americas, got its English name of “wild turkey” stem from convoluted colonial trade routes. Fifteenth-century Turkish merchants imported a type of fowl from Africa to Europe, where it was called “turkey cock.” When Spanish conquistadors imported domesticated M. gallopavo, bred from wild birds by indigenous Mesoamericans centuries before European exploration, confusion between the African fowl and the Spanish avian import led to calling them both turkeys. When English colonists reached America they were astonished to find a wild version of the familiar M. gallopavo.References:Gambino, Megan. What Was on the Menu at the First Thanksgiving?, Smithsonian.comGrace, Catherine O'Neill. 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving(National Geographic Society, 2001)Native Tech, Native American History of Corn